There is a common belief that to leave a mark on the world, one must be a creator—someone who invents, innovates, or produces something entirely new.

Documentation often feels secondary in a culture that celebrates originality, a mere shadow of creation.

What if documenting the world as it is, capturing life in its rawest form, holds as much value, if not more, than creation itself?

Consider the way we understand history. The narrative of our past is pieced together not by those who merely lived through it but by those who took the time to document it. The journals of explorers, the letters of soldiers, and the meticulous notes of scientists are the artefacts that tell us where we came from and who we are. Without them, much of our collective memory would be lost, and the lessons learned from past triumphs and tragedies would fade into oblivion.

“Your journal will stand as a chronicle of your growth, your hopes, your fears, your dreams, your ambitions, your sorrows, your serendipities.”

— Kathleen Adams

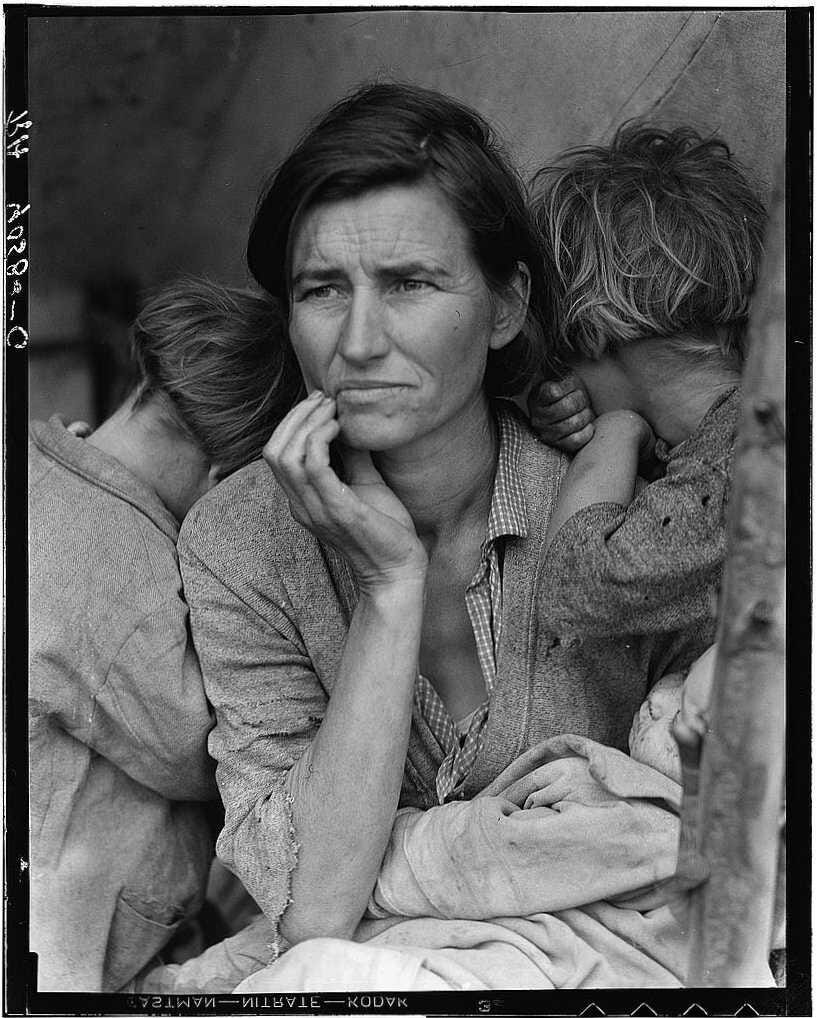

Take, for instance, the work of photographers like Dorothea Lange, whose images of the Great Depression have become iconic representations of that era. Lange did not create the suffering she captured, nor did she invent the resilience etched into the faces of her subjects.

She documented the reality before her, turning life's mundane and often overlooked aspects into something significant. Through her lens, the world was forced to confront the harsh realities of the time, leading to greater awareness and, eventually, change.

Documentation, in this sense, is a form of storytelling. It is not about inventing new stories but about capturing the stories that already exist, making them visible to those who might otherwise overlook them. It is about bearing witness to life in all its complexity and recognising the value in the ordinary.

In a world obsessed with novelty, documentation reminds us that not everything needs to be new to be valuable.

The line between creation and documentation is not always clear. After all, isn't a well-written diary or a carefully composed photograph a form of creation? This blurring of boundaries suggests that documentation can be creative in its own right. How one chooses to document—what details to include, what moments to freeze in time—requires an eye for storytelling, a sensitivity to the nuances of life that is a creative act.

“We’re drawn to making our mark, leaving a record to show we were here, and a journal is a great place to do it.” — Keri Smith

Think of the natural world and the work of botanists who spend their lives cataloguing species of plants and animals. They are not creating new life forms, but their documentation is crucial for the preservation and understanding of biodiversity. Observing, recording, and sharing these findings helps maintain the balance of ecosystems and ensures that future generations can benefit from this knowledge.

The same could be said of cultural anthropologists who document indigenous peoples' rituals, languages, and customs. Their work is not an act of creation but preservation, safeguarding the diversity of human experience.

We live in an age where the ability to document has always been challenging. With smartphones in our pockets, we can capture moments with the tap of a screen, share our thoughts instantly on social media, and contribute to the collective memory of our time. Yet, the ease with which we can document also raises questions about its quality and intent.

“Write hard and clear about what hurts.” – Ernest Hemingway

Are we documenting to understand, to preserve, to share something meaningful? Or are we merely adding noise to an already cluttered digital landscape?

In this context, the value of thoughtful documentation becomes even more apparent. It's not enough to capture or record; documentation should be deliberate, with an eye toward the future.

What will this photo, this journal entry, and this video tell those who come after us? Will it help them understand what life was like in our time, what mattered to us, what we feared, and what we loved?

In documenting the world, we create a bridge between the past and the future. We become the custodians of memory, the keepers of stories that might otherwise be lost.

In doing so, we contribute to humanity's ongoing narrative—not by creating something new but by preserving what is already here.

Sometimes, our most significant contribution is not in inventing the next big thing but in ensuring that the stories of our time, the details of our everyday lives, are remembered.